High Life (2018, France)

High Life (2018, France)

Director: Claire Denis

Writers: Claire Denis and Jean-Pol FargeauWomen in the crew: Isabel Davis, Julia Balaeskoul Nusseibeh (exec. prod.); Klaudia Smieja (prod.); Fee Buck, Beata Rzezniczek (line prod.); Mela Melak (prod. design); Susan Gohsmann (set decoration); Judy Shrewsbury (costume design); Laure Monrréal, Mélanie Bigeard (1st AD); Katharina Meyer Josten, Juliette Picollot, Malgorzata Suwala (2nd AD); Kamila Tarabura (3rd AD)

Available to stream/rent/buy: https://www.justwatch.com/uk/movie/high-life-2018

This review contains **SPOILERS**

Review:

Review:

High Life is European art house director Claire Denis’ first English-language film and surprisingly fronted by international Hollywood star (and former sparklepire) Robert Pattinson. The film was released a few weeks after I completed teaching a course on women in science fiction and began my own journey into the world of women-directed science fiction. High Life is not an easy watch, especially on its first viewing. It is a space movie that purposely disrupts expectations, but its focus on nature, orgasms, sexual politics, isolation, and (lack of) bodily autonomy mark it as part of Denis’ existing cinematic oeuvre.

Denis’ work is often considered difficult to access with its tendency towards slow-paced, nonlinear narratives (she writes in ellipses, often “with a piece missing” from the story). and her often ruthless revisioning of popular genres. It could be argued that this is not her first dabble in SF: Trouble Every Day (2001) is an erotic horror based around a science experiment gone wrong, an experiment that creates humans for whom desire for the flesh becomes literal (cannibalism). Similarly to High Life, we wonder whether Denis intends to contribute to the chosen genre or if these genre interventions should be understood as arthouse/auteur parodies of the boundaries and expectations of genre fiction.

High Life works outside of many of the conventions of mainstream science fiction but it is immersed, as Trouble Every Day was, in iconic horror, in references to major genre-defining visual SF texts. Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) is a major touchstone for Denis both visually and philosophically—the story of a dingy, battered future and unknowable other revels in the mundanity and madness that long-term space habitation must inevitably entail. This is an existential gloom that Tarkovsky explored as rejection or perhaps a reply to the utopian sterility of the future of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and the fleeting dystopias of mainstream space operas of the 1970s.

“What is nothing, when there is no time and no space?”

– Claire Denis, TiFF 2018

High Life is set on a spaceship on a one-way mission to gather data from black holes as a possible alternative form of energy. Here, space is literally a prison as the inhabitants of the ship have all been convicted of violent crimes and have traded death row for this government-sponsored experiment. The elegant lo-fi sci-fi aesthetic allows for a more existential exploration of the psyche in isolation. The human mind unoccupied in the void of space is the ultimate prison when there is no hope of return. Where the elastic cosmic nothingness of time and space was too much for the people on the Aniara in Aniara (2018)—theirs was meant to be a finite journey from Earth to Mars—it provides a curious comfort for much of High Life. The tender scenes with Monte (Patterson) and his daughter Willow (baby: Scarlette Lindsey, child: Jessie Ross) show their routine and frustrations, but these are occupied minds unexpectedly growing, learning, and loving together.

Monte is a murderer; as a child he took revenge on the friend who killed his dog. We assume from the little given away by Monte in flashbacks that he has been isolated all of his life, given a life sentence as a minor. It is hard not to read the film as a critique of the US prison system where sentences can be handed out that do not allow for redemption and juveniles can be sentenced to life without parole. The spaceship prison offers Monte a greater sense of freedom, and later purpose and hope with the unexpected delivery of his daughter.

One of the few areas of the ship that doesn’t replicate the dilapidated images of humdrum space travel is the garden allotment—like Solaris, High Life’s ship is more dingy public transport chic than sparkling Kubrickian luxury. The garden offers another reference to a classic text, here Silent Running (1972), in which the last of Earth’s forests are jettisoned into the relative safety of space in giant geodesic domes (I adore the opening scene). The garden seems to be part of the experiment for long-term survival in space.

André 3000 [aka André Benjamin] plays Tcherny who tends to the garden that ultimately becomes his gravesite. He commits suicide and, per his request, Monte commits his body to the garden; Monte, as the last surviving prisoner, takes over as gardner. In one striking conversation these men talk about why they joined the mission: for Tcherny it is about giving his family something to be proud of (redemption), whereas Monte’s isolation and social separation has been lifelong until he goes into space.

Tcherny: “I’d rather sink into the Earth after I’ve lost you than to sit around and grieve once you’ve gone off into your destiny.”

Monte: What are you talking about?

Tcherny: It’s what my wife told me. I told her I was doing all this for her and our son, to turn our shame into some type of glory, you know? She says that this mission was like burying her twice and that my idea of glory was bullshit.

Denis claims that High Life is “not about space. [because] There is no hope to escape. It is the ultimate jail” (initially the script was to be co-written with Zadie Smith but apparently they fought over many issues including the ending, where Smith wanted the hope of return). High Life is a prison movie.

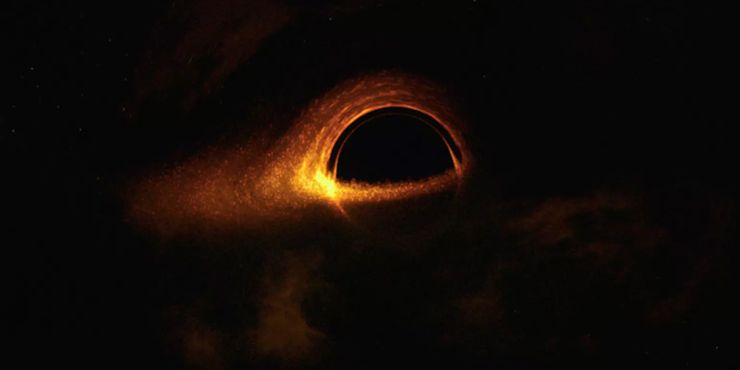

Denis did work closely with astrophysicists and astronauts to ensure that space in High Life was “as close as possible” to reality. The startlingly accurate images of the black hole that are created—Denis refers to the image as the crocodile’s eye—makes this an interesting approach to representing space as both science and art. Part of the inspiration and test space for the yellow-tinged but beautiful lighting and visual design came from a collaboration with visual artist Olafur Eliasson for his 2014/15 exhibition Contact (Foundation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France). Their short film/installation is also called Contact where the artists creatively and abstractly explore ‘their common fascination with phenomena that have not yet been fully explained by science – such as black holes’.

Denis did work closely with astrophysicists and astronauts to ensure that space in High Life was “as close as possible” to reality. The startlingly accurate images of the black hole that are created—Denis refers to the image as the crocodile’s eye—makes this an interesting approach to representing space as both science and art. Part of the inspiration and test space for the yellow-tinged but beautiful lighting and visual design came from a collaboration with visual artist Olafur Eliasson for his 2014/15 exhibition Contact (Foundation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France). Their short film/installation is also called Contact where the artists creatively and abstractly explore ‘their common fascination with phenomena that have not yet been fully explained by science – such as black holes’.

Contact – A film by Claire Denis from Studio Olafur Eliasson

As part of pre-production there was a visit to the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne where main cast members trained on the same installation as astronauts bound for the International Space Station. They experienced simulations of the dynamics and routine needed for survival on the ISS. Astronaut Instructor and Simulation Director at the centre—Laura André-Boyet—acted as science advisor to the film. As she notes: “High Life is not necessarily about scientific exactitude. Claire probably used Space scientific expertise to extract what was inspiring for her and not necessarily to reproduce it with accuracy.” But science on screen is not always indelibly tied to accuracy; instead it is woven into the story as a discussion of futures, ethics, and human experiences. Yet, the striking intersection of art and science in the prophetically accurate images of black holes and the reality of the astronauts’ behaviour and routine should not be dismissed.

The visual design of High Life is also stunning, much like the visual contemplative storytelling of Lucile Hadžihalilović’s Évolution (2015) where audiences must fill in the gaps and create the narrative from the fragments that Denis deigns to offer. Amongst the scenes of violence and sex there are beautiful images of the garden and the tender relationship between Monte and his young daughter. As Willow grows the audience is given flashbacks to a time when Monte was one of many prisoners but was perhaps far more insular—both sexually and socially celibate.

The opening of the film which appears almost as surveillance footage of Monte (Pattinson) raising his daughter and repeating the routine of survival on a spaceship. It is just them and this close bond that is our entry point into the High Life. In flashbacks—the sense of time is lost—the other characters die off one by one, either from murder, suicide, or natural(ish) causes. Chandra (Lars Eidinger) develops leukemia due to radiation and has a stroke, but is then euthanised by the ship’s doctor, and the pregnant Elektra (Gloria Obianyo) delivers a baby who dies and then dies herself soon after.

The death-row prisoners have donated their bodies to science while they are still alive. Not only in the experiment of the one-way exploratory voyage and self-sufficiency, but also as subjects for the onboard scientist child-murderer/insemination specialist Dr Dibs (Juliette Binoche). She too is a sentenced criminal but has been charged with her own exploratory mission into intergalactic insemination and childbirth. Any surviving children will be collateral damage: their survival is punishment for the sins of the mother and father (and their doctor). Sex between the prisoners is forbidden and all but the celibate Monte seem to use the efficiently named Fuckbox for sexual release (and collection of samples). The need for sexual pleasure in space is paired with the need for sustenance provided by the garden. Interestingly, they are the only two spaces that deviate in terms of design from the rest of the utilitarian prison ship.

Eleckra and later Boyse’s (Mia Goth) pregnancies are the result of experiments by the witchy Dr Dibs who is obsessed with making and stealing children (even though she killed her own biological children). She inseminates the female prisoners with sperm taken with or without the consent of the male prisoners. Dibs increases prisoner sedatives following an attempted rape and murder, but her motivations are predatory rather than protective as she rapes Monte and steals his sperm while he is unconscious. Boyse carries the baby to term but is not her mother beyond biology—her story is not altered by the child, choosing a risky and ultimately deadly mission over staying onboard. Willow’s parentage is a revelation from a dying Dibs; Monte was unaware that he had contributed to her creation but, unlike Boyse, he does choose to become a father rather than rejecting the innocent infant. The ‘present day’ scenes show Monte’s acceptance, trust and love for Willow, and their final act together is as beautiful as it is baffling.

What to watch next from Claire Denis:

One of the few women directors of SF to have an extensive filmography filled with critically acclaimed cinematic masterpieces. She did not start directing feature films until she was 42 with Chocolat. I clearly enjoyed (if that is the right word) High Life and I think it is a pretty good entry point for someone who hasn’t seen her French work. This is only a small selection of Denis’ feature films (13 fiction, 2 in production + shorts, TV work, and documentaries):

Chocolat (1988)

Beau Travail (1999)

Trouble Every Day (2001)

35 Shots of Rum (2008)

White Material (2009)

Bastards (2013)

Let the Sunshine In (2017)

Further reading:

Video essayist Luís Azevedo The Sensual World of Claire Denis (2019) https://lwlies.com/articles/the-sensual-world-of-claire-denis-video-essay/

Sonia Shechet Epstein (2018). Claire Denis’ Science Consultant Talks About High Life. Sloan Science and Film [online]. http://scienceandfilm.org/articles/3169/claire-denis-science-consultant-talks-about-high-life

David Jenkins Interview with Claire Denis for Little White Lies (2019) https://lwlies.com/interviews/claire-denis-high-life-robert-pattinson/

Elena Lazic’s interview with Claire Denis for BFI in the run up to the Summer 2019 retrospective The Original Sin of Claire Denis https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/interviews/no-fear-no-die-interview-claire-denis

Sophie Monks Kaufman’s gorgeous review from Little White Lies https://lwlies.com/reviews/high-life/

Yasmin Tayag (2019). How High Life created the black hole that looks just like the historic photo. Inverse [onine]. https://www.inverse.com/article/55087-high-life-claire-denis-aurelien-barrau-got-black-holes-right

Natalie Winkleman (2019). Director Claire Denis on Designing a “Pro-Sex” Space Prison. The Slate [online] https://slate.com/culture/2019/04/high-life-claire-denis-director-interview-sex-space.html

One thought on “#WomenMakeSF Review (12): High Life (2018)”